What draws us back to Ridley Scott’s masterpiece again and again?

By Paul Dunne

26th April 2024

“That’s not our system…”

(Ripley)

In cinema, everyone can hear you scream.

And in some cases, they might just want you to. The landscape of genre-specific cinema (horror, sci-fi) was changed more than once in the 70s. In 1975, with the release of Jaws, in ‘77 with the release of Star Wars. In 1979, a film was released that drew on the used future of Star Wars and the monsterous, unstoppable engine of Jaws to create a unique, alchemic creature. At the time, films were going through metamorphesis. Shedding one skin and becoming something new, more robust, aggressive. The form was moving from the art-first, French influenced character-driven intellectualism, and re-engineering those traits, adding a deus ex machina of fantastical creatures and cruel nature. There was almost a reactive regression taking place. American fim-makers looked to past genres, dying giants, to fuel their modern drives. Jaws held on to the romantic characterisation of classical cinema, like the John Ford’s Westerns and fused it with a slightly more hip, ‘70s feel simply as a by-product of it’s year of origin and the genius of Steven Spielberg. Star Wars would take the central conflict of those westerns and their focus on homesteaders, whilst delivering a very traditional story of Good Versus Evil.

But although this was distinctly American journey, with American voices creating American milieus (even if they were set in a Galaxy Far, Far Away), it would take a British director to retrofit The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Jaws, Star Wars and ‘50s sci-fi that soaked up the threat of Russia and ‘The Bomb’ and gave us paranoia in the streets. That paranoia was about distilled down to a more personalised focus, from the masses to the small crew of a towing vessel in space. On board were a crew of truckers, sleeping as deeply as their voyage. But sleepers, like the audience, were about to be awakened, as was something else. Something deep in our subconscious. Something familiar yet distinctly… ALIEN.

“My God…”

(Dallas)

When Alien chest-burst it’s way on to screens it was a beautiful collision of art and viscera, intellectual prowess and recoiling, clenching reaction. Could we have finally have found a film that was tapped into the life of the mind, the imagination and the physical thrust of the body? Director Ridley Scott certainly felt so. Speaking in 1999 about the ideas behind his approach, the director said: “I always wanted to keep it tight and only show what you want to see. Because the mind is stronger than anything else, so if you think you’ve seen something…” But he was not content with keeping it all inside. He wanted to build, to make, to craft. Fusion of genre wasn’t the only alchemical mix happening in Shepperton in 1978. Scott brought together the art-design (emphasis on art) of Les Dilley, Michael Seymour and Swiss artist H. R. Geiger, whose book Necromicon included a painting whose sexuality and darkness penetrated first writer Dan O’Bannon’s mind and then Ridley Scott’s. Geiger was sequestered in Shepperton away from the other designers and builders on the film. Strange black magic took place behind the closed doors that only Ridley Scott could step behind at 5pm each day. Bones were brought in. Everything was painted black. Everything was wet, sweating with unknown respiratory systems from strange life forms. Would Geiger’s rumoured opium habit leaking through to the celluloid?

Elsewhere in the studio, Dilley and Seymour, along with costume designer John Mollo were inhaling their own kind of opioid vapor, lit by the fire of Scott’s promethean lightning bolt, given to him by French artist Jean Girard, whom we all know as Moebius and others from the pages of French comics anthology, Metal Hurlant (Heavy Metal). And of course his own past and upbringing in the British coastal town of South Shields in Tyneside, Tyne & Wear and his time at the Royal College of Art in London. Dilley and Seymour were aided by Roger Christian, who had worked on Star Wars, and Ron Cobb who knew how everything worked, and together with Scott they constructed a human environment, wih almost no humanity. Vacuum-formed plastics coated surfaces. Ageing aircraft parts welded onto walls and control panels. As Shallow Grave and 28 Days Later director Danny Boyle would say in the 1999 C4 documentary, Shock and Awe: The Return of Alien, “Everything is in a Post industrial age where the technology we’ve built for ourselves has begun to rust. Ridley wasn’t afraid to clash together artistic obseession, his messianic attention to detail and atmosphere, and commercial success. The need to deliver certain things to an audience at certain times.” Scott’s directorial style allowed for long, quiet still sequences by short sharp shocks. “I decided never to rush it”, Scott said in 1999. “Give Alien a cadence, a pace – because the pace, eventually, will get to you. The music had the same cadence. There’s a certain evenly paced, relentless metronome.”

“You don’t understand what you’re dealing with. A perfect organism. It’s structural perfection is matched only by it’s hostility.”

(Ash)

The script, as written by Dan O’Bannon and Ron Shussett, then parsed down by Walter Hill, had a ticking momentum, driven by one thing, that Scott got behind immediately: “The Engine was designed and the whole story is based around that engine, and that engine is: What happens when this thing gets aboard. And everything that happens is subsequent to that.” Alien is a machine made of both inorganic and organic parts. Geiger fused both of those to create a creature that spoke to our collective unconscious. You cannot explore Alien as film without exploring it’s sexual connotations. The male fear of penetration, of rape and the turning table of unwanted sexual attention practically unheard of in film at the time is all over Alien. Even if those discussions fall into a simplistic arena – what is the creature but a hostile, sentient, blind penis? - the conversation the film generates has depth and range to roam.

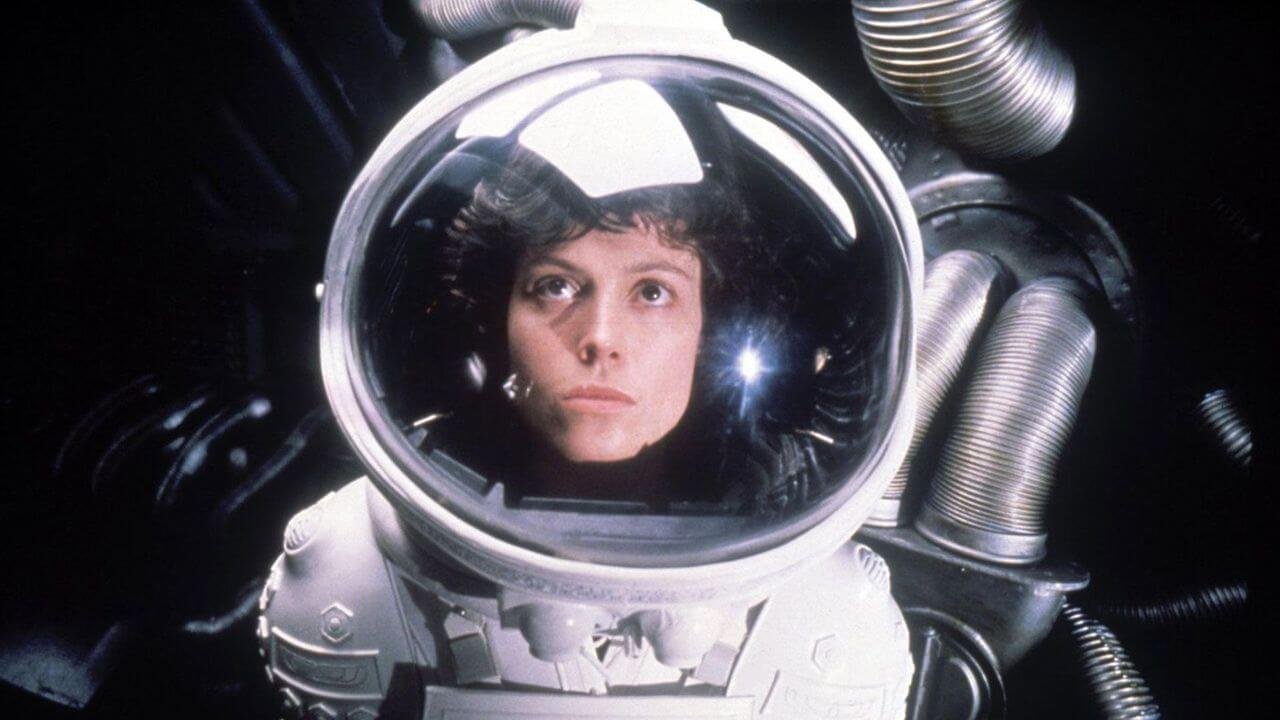

For the inorganic, one can look to the omnipresent yet rarely seen ‘Company’, Weyland Yutani, whose unseen hand is crushing the working classes aboard the Nostromo. Even their stealth agent, the science officer Ash, counters any attempt at dissent. When Yapphet Kotto’s immense, throaty, booming Parker and Harry Dean Stanton’s slight, relaxed Brett argue for more money when the ship is repurposed for potential rescue mission, it’s Ash who shuts hem down with a reminder about the clause in their contract that compels them to alter their course. When Ripley deciphers the beacon that brings them to LV-426 as a warning rather than a distress call, it’s Ash who stops her from going out after Dallas, Kane and Lambert. And when that trio returns to the ship with the Facehugger attached, it’s Ash who countermands Ripley’s quarantine order. The Alien is almost incidental. Ash and therefore the company is the instigator of the death that ensures. Special Order 937: All Other Priorites Rescinded.

“God Damn it, Parker! Will just listen to me!”

(Ripley)

Scott and editor Terry Rawlings, who had never edited a film but was an experienced sound mixer, knew how to create impact within the construct of the genres they were working in. As Scott would later put it, “You can feel the buzz in the editing room, you know?” Like Hill working on the screenplay, Scott and Rawlings knew the benefit of removing things. Watch the film’s key moment, the infamous and still highly effective Chestburster scene, and pay attention not what’s there, but what isn’t: The Score. Jerry Goldsmith created a lush, atmospheric and at times experimental score. But for the film’s key scene, Scott insisted on just atmospheric sounds, effects and the sound of screaming. Scott’s feelings on the use of music were clear: “It’s a lesson in the minimalist use of score”, the director said 20 years after the film’s release. “You only use the score when you need to use he score, so when the score comes in it’s always for reason. The tendency today is to slather the thing in sound and music. Picking up a cup of coffee is scored! Consequently, you use up your score. You use up the power of music. There are tracks of silence in Alien. And when something’s gonna happen, you’re warned. But you’re warned in the most beautiful, elegant way.”

Forty five years after it graced cinemas, we’re still unnerved by Alien’s silence, it pace and its beast. Perhaps it’s that pace, along with with the film’s crafted, constructed, tactile, real textures and its intelligent subtext, wrapped in the egg of B-Movie pleasures that gives it allure and timelessness? As Danny Boyle remarked 25 years ago, “For anybody doing horror, it’s your first port of call. No matter when you watch it, you forget, almost immediateley, the context, the time you’re watching it in.” For forty five years, the screaming in space has never stopped. I hope it never will.

Alien is available on Blu-Ray and 4K now.